MONU #33

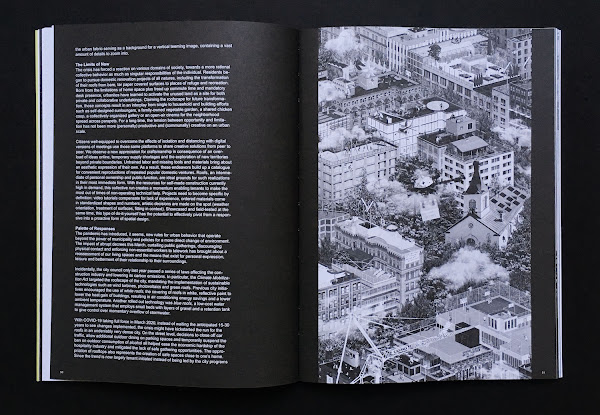

MONU #33: Pandemic UrbanismMagazine on Urbanism, October 2020Paperback | 7-3/4 x 10-1/2 inches | 128 pages | English | ISSN: 1860-3211 | $23.99 ISSUE CONTENTS: Quarantines and Paranoia - Interview with Beatriz Colomina by Bernd Upmeyer; On Constructing a Semana Santa by Ana Morcillo Pallares; Here Not There Urbanism by Jessica Bridger; Lockdown London: Tale of the Tape by Peter Dench; Grasping for (Fresh) Air: Exposing the Inherent Conflict of Public Interiors by Dalia Munenzon and Yair Titelboim; Balco(n)vid-19: How the Pandemic Can Be Hacked by Michaela Litsardaki; New Top City by Eventually Made (Sebastian Bernardy and Vincent Meyer Madaus); Pestilential Cities - Cities as Spheres for Pathogens, Epidemics and Wellbeing by Ian Nazareth, Conrad Hamann and Rosemary Heyworth; The Great Emptiness by Carmelo Ignaccolo and Ayan Meer; Eternal Silence by Nadia Shira Cohen; Isolation and Inequality - Interview with Richard Sennett by Bernd Upmeyer; Transformation Towards Community Resilience: New Urban Visions by Jan Fransen and Daniela Ochoa Peralta; Drivers of Change for the "New" in the "Normal" by Alexander Jachnow; Real Estate Art in the Age of Pandemic by Kuba Snopek; Bringing about the Adaptive Street by Joshua Yates and Janna Hohn; Can the Pandemic Situation Generate Walkable Cities? by Leticia Sabino and Louise Uchôa (SampaPé!); The Total House During and After Coronavirus: A Virtual Place and More by Anna Rita Emili (altro_studio); Medial Territories by Michele Cerruti But; Augmented Domesticities - The Rise of a Non-Typological Architecture by Pedro Pitarch REVIEW BY EMILIE STECHER: In March 2020 our perception of the urban was suddenly limited to the square meters of our flats. Working, learning, meeting friends, or going to a concert — everything took place within our four walls. Finally, during the summer, after months of isolation, we slowly made our way back into the city, craving social contact. Now we are watching, in real-time, our metropolises being transformed. Bike lanes pop up on the surface, restaurants expand onto the pavement and play-streets find their way into our new perception of the urban area. If illnesses like tuberculosis were "house problems," Covid-19 is a "city problem," as Beatriz Colomina describes in her interview in MONU #33. Will this pandemic be a revolution for the city of the future? The latest issue of MONU, Pandemic Urbanism, gets the discussion started. With distinct views from different perspectives, artists, urbanists, researchers and sociologists offer an insight into their field. They show what they have experienced during the last months and analyze what they think the future might hold. To get a good basis for discussion, the issue provides knowledge about the historical influences of illnesses on cities and the previous drivers for change. Furthermore, it presents documentations and changes that the urban environment experienced during the last months and includes visions for the future. With these diverse perspectives, the issue tries to figure out what urbanism was, is, and will be. A reoccurring theme is the relation between the private and public. The reader can dive into a vivid description of the religious Easter ritual of Semana Santa, the holy week, which took place on a balcony in Spain. In a research study about the use of balconies during the lockdown, one can get lost in the imagination of non-balcony owners. The revival of rooftops in New York is presented by a fascinating illustration showing imaginative uses for the "new top city," offering new discoveries again and again. Through new uses implemented into the domestic space, Pedro Pitarch calls for the end of the Architectural Typology, which ought to replace programs with architectural performances. Bedrooms are no longer only used for sleeping and kitchens for more than cooking. This thought continues in the project of the "total house" of Anna Rita Emili, where space is created through laser projections. She sees a decrease in distance between the private and public and as a result the home transforms into a multifunctional space where all life takes place. Through smart working there is more time dedicated to recreation and hobbies and furthermore to fall in line with our biorhythms. Working from home and homeschooling let this usual border between the private and public disappear. In the interview Beatriz Colomina says that the seemingly small-scale impact of working from home can have a huge impact on the shaping of cities. With all the empty office buildings in the center, we would have to rethink the city itself. Colomina is not alone in rethinking urban space. With absent tourists, a lot of Italian city centers were abandoned and showed their urgency in designing for residents and not for tourists. The silence in Rome is beautifully captured in a photo essay. A dancing couple shows the freedom that lies within the new vacancy. I assume the article by Jessica Bridger, which is a

MONU #33: Pandemic Urbanism

Magazine on Urbanism, October 2020

Paperback | 7-3/4 x 10-1/2 inches | 128 pages | English | ISSN: 1860-3211 | $23.99

INSIDE THE ISSUE:

ABOUT MONU:

PURCHASE LINK:

|

| Balco(n)vid-19: How the Pandemic Can Be Hacked by Michaela Litsardaki, p. 42-43 |

|

| New Top City by Eventually Made (Sebastian Bernardy and Vincent Meyer Madaus) p. 50-51 |

| ||

Eternal Silence by Nadia Shira Cohen, p. 70-71

|