Race and Modern Architecture

Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, Mabel O. Wilson (Editors)University of Pittsburgh Press, July 2020Hardcover | Page Size inches | # pages | # illustrations | English | ISBN: 978-0822966593 | $45.00PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION: Although race—a concept of human difference that establishes hierarchies of power and domination—has played a critical role in the development of modern architectural discourse and practice since the Enlightenment, its influence on the discipline remains largely underexplored. This volume offers a welcome and long-awaited intervention for the field by shining a spotlight on constructions of race and their impact on architecture and theory in Europe and North America and across various global contexts since the eighteenth century. Challenging us to write race back into architectural history, contributors confront how racial thinking has intimately shaped some of the key concepts of modern architecture and culture over time, including freedom, revolution, character, national and indigenous style, progress, hybridity, climate, representation, and radicalism. By analyzing how architecture has intersected with histories of slavery, colonialism, and inequality—from eighteenth-century neoclassical governmental buildings to present-day housing projects for immigrants—Race and Modern Architecture challenges, complicates, and revises the standard association of modern architecture with a universal project of emancipation and progress. Irene Cheng is an architectural historian and associate professor at the California College of the Arts. Charles L. Davis II is an assistant professor of architectural history and criticism at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Mabel O. Wilson is the Nancy and George E. Rupp Professor at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation and a professor in African American and African Diasporic Studies at Columbia University. REFERRAL LINKS: dDAB COMMENTARY: Recently I watched the Back to the Future trilogy with my daughter, who is the same age I was when the first film came out. There's a scene in the second film in which Michael J. Fox's character, having returned to 1985 from a futuristic 2015, goes to his suburban home in Lyon Estates but finds it in a dramatically different state from when he left it: graffiti is on the subdivision's gates, "for sale" signs and abandoned cars litter the street, stray dogs roam about, a transmission tower sits in his backyard, and an African American family is living in his home. My daughter and I rolled our eyes in unison at the last part of this filmic dystopia caused by a power-hungry time traveler. It spurred us to chat about the obvious racism of the scene, particularly in terms of a Black family and neighborhood representing crime, decay, despair ... representing basically the opposite of the idyllic upbringing of the main character and most people in the film. While my daughter and I found the scene appalling, I can't say that I felt the same way when I watched the film as a teenager. Sure, now I'm a lot older and a little bit wiser, but I think stronger reactions to racism today are due, in part, to many more conversations being had about race, especially African Americans being treated unfairly by white people in power. Even if I would have recognized the racism of that scene as a child, like my daughter did, I probably would not have known then how government policies made it close to impossible last century for a Black family to own a house in a desirable area rather than being segregated into a ghetto. So the insertion of a Black family in Back to the Future Part II is not only a shallow racist representation, it is an acknowledgment that the policies that made such a representation tenable (the de jure and de facto segregation, as explained by Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law) are acceptable, that they don't need to be challenged. Even the head of the unnamed family yelling, "And you tell that realty company that I ain't sellin'," which has been recognized as a form of blockbusting in the film's alternate reality, doesn't help counter the subtext of the scene. The sequel to a Hollywood blockbuster is far removed from a book arising from an academic symposium and online research project, but just as a film can now be analyzed in terms of race when it might not have been initially, the history of modern architecture can — and should, the editors contend — be understood as well in terms of race. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson clearly state this aim in the introduction to Race and Modern Architecture: "The book's goal is to demonstrate that attention to race is no longer optional in the study of modern architectural history." As such, this means the eighteen scholarly contributions that follow the introduction are a starting point, not a comprehensive take on a complex and complicat

University of Pittsburgh Press, July 2020

Hardcover | Page Size inches | # pages | # illustrations | English | ISBN: 978-0822966593 | $45.00

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

REFERRAL LINKS:

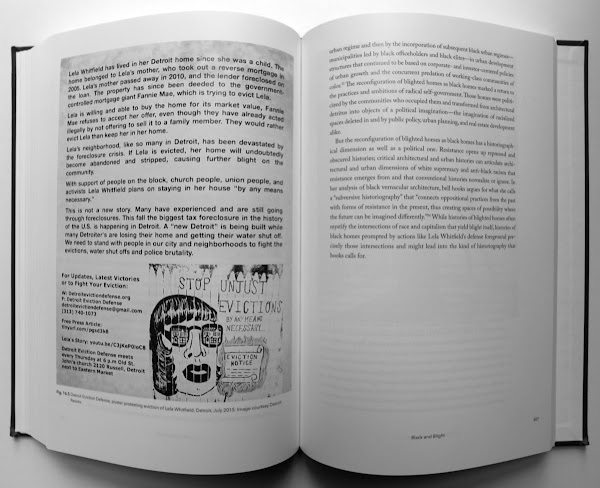

SPREADS: