From the middle of March, when a family emergency put this blog on hiatus, until the middle of July, when a funeral mass was held for my dad, my life was split almost evenly between my home in New York City and my parent's home in Central Florida. The emergency in March was an incident putting my father in the hospital, and it was followed by numerous diagnoses, the need for him to go into assisted living, and eventually him going back into the hospital, where he died — peacefully, with me, my mother, and my sister at his bedside. Back in March I anticipated, even with his diagnoses, to be helping him in various capacities for a few years, not just a few months. They were difficult and taxing months that found me as relieved as saddened when he passed; the obvious pain and frustration he felt are gone, but memories of him remain and in some ways are stronger and more prevalent now than before.

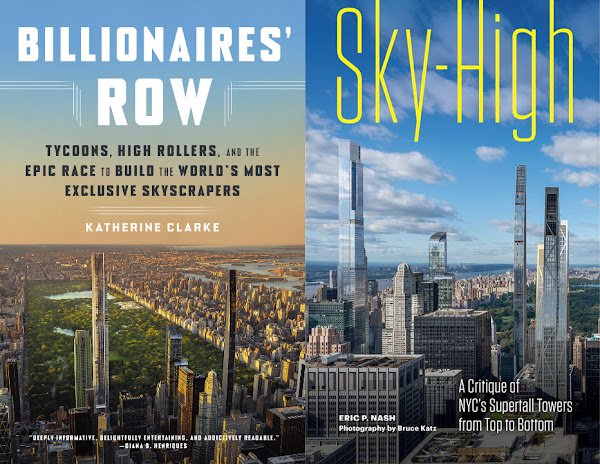

In the prologue to

Billionaires' Row, Wall Street Journal reporter

Katherine Clarke describes the construction of 40 Wall Street, the Chrysler Building, and the Empire State Building nearly a full century ago as "a veritable race to the sky as wealthy titans of industry vied to build a succession of towers, each taller than the last." (It's a race

recounted by Neal Bascomb in

Higher: A Historic Race to the Sky and the Making of a City back in 2003.) The brief historical anecdote gives the new book an angle, one expressed clearly in its subtitle. Yet I have a hard time buying that the developers of One57 (Gary Barnett/Extell), 432 Park Avenue (Harry Macklowe and CIM Group), 111 West 57th Street (Michael Stern/JDS), 220 Central Park South (Steve Roth/Vornado), and Central Park Tower (also Barnett/Extell) were involved in any sort of race, figurative or otherwise. I've been paying attention to this handful of buildings along Billionaires' Row as long as Clarke has, though not nearly to the same in-depth and insider degree as her, I'll admit, yet I still struggle to find a correlation between these towers and the Manhattan office buildings from the 1920s and 30s. Yes, there is synergy in that each grouping was born from the circumstances of the time (architectural, technological, economic, etc.), but the only "race" I find is, not between the developers themselves, but between the developers and the market — the developers had to quickly sell their eight- and nine-digit aeries before the market for them dried up. If anything, the assemblage of these five towers sitting mainly along 57th Street, a wide street they exploited for unused FAR (floor-area ratio) and reshaped in the process, are less an example of competition and more so an instance of geographical synergy, like a row of car dealers along a busy thoroughfare.

People looking for a behind-the-scenes look at the development of these Billionaires' Row towers will be very happy with Clarke's book. The focus is squarely on the four men listed above, the developers behind the five towers. Readers will learn a little bit about the architecture, interior design, engineering and other physical attributes of the towers, but they will learn a lot more about the legal and economic means of how each individual tower happened, as well as the personalities of those men and the people they had relationships with, both business and personal. I have given walking tours of 57th Street and other parts of the city where luxury residential towers are in abundance, and while I tend to focus on aspects of architecture, engineering, and zoning, I never forget to mention how much celebrities and other high-worth people pay for the units; slenderness ratio is exciting to some, but the most audible gasps come from patrons hearing about condos selling for tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. Similarly, Clarke knows her audience; she is attuned to the public's interest in money — plus how much people love to hear about bad things happening to rich people. So the book, a chronological account spanning just over a decade, has plenty of information on the money problems, leaks and creaks, lawsuits, and personal squabbles playing out over that time. If you like hearing that sort of thing, you'll love this book.

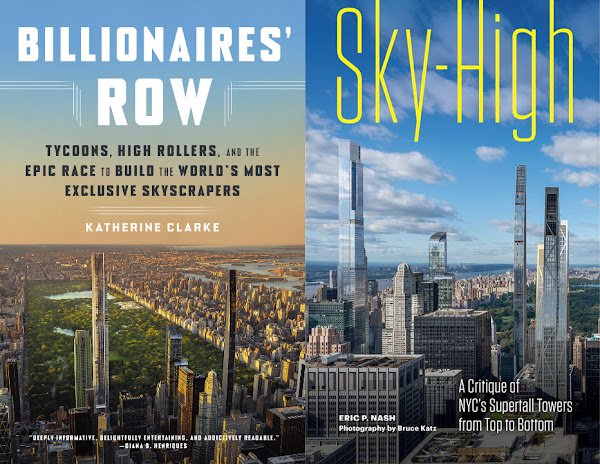

Although I found

Billionaires' Row at a used bookstore a few weeks ago, it was released just last month, exactly two weeks before

Sky-High, by former New York Times writer Eric P. Nash. Was there a publishing race to get the first book about Manhattan's supertall towers for the super rich in print? I doubt it, especially since Nash's book has a wider scope than Clarke's, and his book is as much about the photographs by Bruce Katz as it is Nash's critical takes on a dozen 300-meter-plus towers, residential and otherwise, in Manhattan

and Brooklyn. Also, the two books lag two years behind Andi Schmied's wonderful and artsy

Private Views: A High-Rise Panorama of Manhattan (VI PER Gallery, 2021), arguably the first book on the phenomenon. Last year, well before it was published, an editor at Princeton Architecture Press sent me a preview of

Sky-High for a potential blurb on the cover. It wasn't used (the book ended up without any blurbs), but this is what I wrote:

"I don't know whether to join Eric P. Nash's fact-filled, opinion-laden chorus and decry some of the dozen supertalls that have reconfigured New York City’s skyline this century, or adore them all through Bruce Katz's loving wide-angle lens. All I know for sure is that this is a much-needed book."

Now seeing the book in print, sent to me recently by the publisher, I stand by my statement and its implication that it's nigh impossible to reach any conclusions on the phenomenon of NYC skyscrapers this century when imbibing critical takes, mainly of the aesthetic variety, joined by architectural photography presenting the buildings in the best possible manner. No wonder the back-cover description calls it "part architectural guidebook and part critique." Nash's thirteen numbered chapters are grouped in three parts — "A Short History of the Tall Building in New York City," "Supertalls," and Is Bigger Better?" — with Katz's documentation of the dozen towers inserted as project spreads with black backgrounds. The latter would seem to demarcate photo contributions from text, but more of Katz's photographs are provided alongside Nash's text, making the book more visual than textual. As such, the tug of war between verbal critique and visual praise is near constant.

Unfortunately, in the last part of the book, when Nash states that "the real question skyscrapers of any height pose is [...] how they impact the quality of street life," very few photos of that condition, where a skyscraper meets the sidewalk, are provided — and we only see the good examples, including

the pedestrian plaza next to One Vanderbilt. Perhaps this dearth is due to timing (the retail at the base of 111 West 57th is still empty, for instance, while its residential entrance on 58th Street sits behind scaffolding), but perhaps it's an inadvertent commentary on the fact these towers contribute very little to the quality of street life. Yes, 432 Park Avenue has

a nice POPS between the tower and its detached retail component, but 220 Central Park South puts a private drop-off along 58th Street, opposite where Central Park Tower has an entrance to the pricey Nordstrom department store. Most of these Billionaires' Row towers put their loading docks along narrow 58th Street, but photos similar to those

I captured recently would stand out like proverbial sore thumbs in this book. Instead, Nash references Edward Soja, Rebecca Solnit, Shoshna Zuboff, and Henri Lefebvre in a chapter in part three, when he quotes Elizabeth Diller, architect of the near-supertall at

15 Hudson Yards, as saying skyscrapers like 432 Park Avenue and 111 West 57th Street "damage the city fabric." If they do, visual evidence of it is hard to find in

Sky-High.