The Architecture of Health

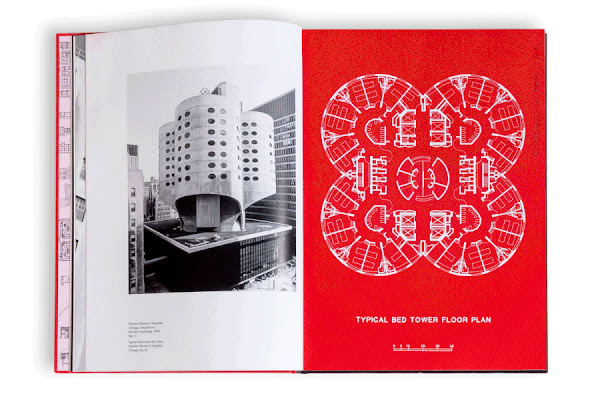

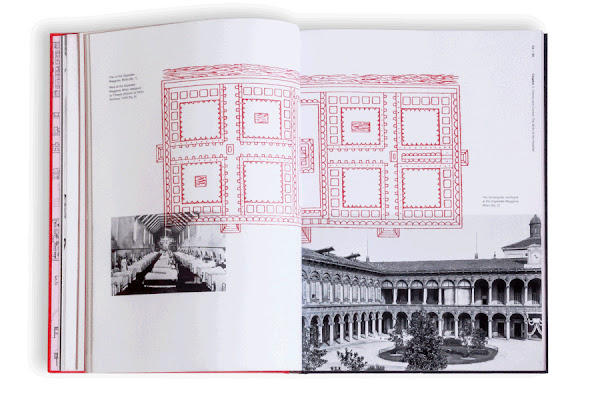

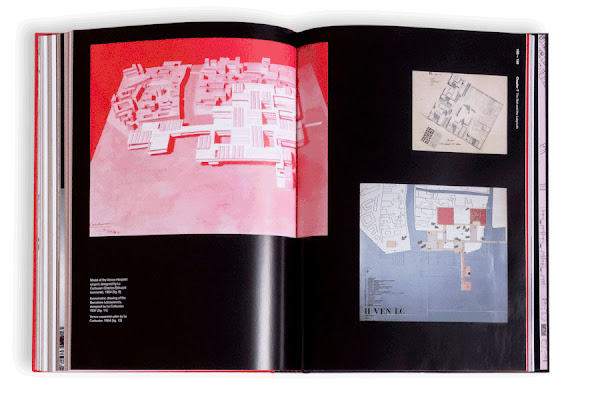

The Architecture of Health: Hospital Design and the Construction of Dignityby Michael P. Murphy with Jeffrey Mansfield and MASS Design GroupCooper Hewitt, November 2021Hardcover | 7-1/4 x 10 inches | 256 pages | 250 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781942303312 | $45.00PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:The Architecture of Health is a story about the design and life of hospitals—about how they are born and evolve, about the forces that give them shape, and the shifts that conspire to render them inadequate.Reading architecture through the history of hospitals offers a tool for unlocking the elemental principles of architecture and the intractable laws of human and social conditions that architecture serves in each of our lives. This book encounters brilliant and visionary designers who were hospital architects but also systems designers, driven by the aim of social change. They faced the contradictions of health care in their time and found innovative ways to solve for specific medical dilemmas. Designers and professionals such as Filarete, Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Albert Schweitzer, Gordon Friesen, E. Todd Wheeler and Eberhard Zeidler are studied here, while the medical spaces of more widely known architects such as Isambard Brunel, Aalvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn and Paul Rudolph also help inform this history. All these characters were polymaths and provocateurs, but none quite summarizes this history more succinctly than Florence Nightingale, who, in laying out her guidelines for ward design in 1859, shows how the design of a medical facility can influence an entire political and social order.The Architecture of Health charts historical epidemics alongside modern and contemporary architectural transformations in service of medicine, health and habitation, exploring how infrastructure facilitates healing and architecture’s greater role in constructing our societies.Michael Murphy, is the Founding Principal and Executive Director of MASS Design Group, an architecture and design collective that leverages buildings, as well as the design and construction process, to become catalysts for economic growth, social change, and justice. Jeffrey Mansfield is a design director at MASS Design Group, a John W. Kluge Fellow at the Library of Congress, and a Disability Futures Fellow with the Ford Foundation, whose work explores the relationships between architecture, landscape, and power.REFERRAL LINKS: dDAB COMMENTARY:Today is the opening of Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics, an exhibition at Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, curated by MASS Design Group and Cooper Hewitt. Presenting "architectural case studies and historical narratives alongside creative design responses to COVID-19," the exhibition is timely and relevant, especially as the world finds itself in a fourth (or is it fifth?) wave of the pandemic, one that is almost guaranteed to keep growing as the omicron variant spreads globally. The exhibition, which I got a sneak peek of yesterday, is accompanied by a book written by Michael Murphy of MASS Design Group, whose first project was a hospital and is one of the few architects I've seen profiled on 60 Minutes. While the exhibition takes a broad design look at health in general and COVID-19 in particular — masks, social distancing markers, medical equipment, furniture, hospitals — The Architecture of Health focuses on the last: hospitals.Although a book such as Beatriz Colomina's excellent X-Ray Architecture examines the relationship between architecture and medicine, which book would one read to gain a comprehensive understanding of the design of hospitals? Murphy admits to a dearth of attention on the typology early in his book, though some of the sidebar citations in the book's eight chapters reveal at least a couple of them focused on hospitals: The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History by John D. Thompson and Grace Goldin (Yale University Press, 1975) and Jeanne Kisacky's Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870–1940 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017). But those titles are outdated and academic, respectively, making the book Murphy wrote with Jeffrey Mansfield and MASS Design Group a welcome addition to scholarship on the subject. It is an accessible history to the design of hospitals while also being, I agree, a way of "reading architecture through the history of hospitals," as the book description attests.Following a prologue on the innovative and much-missed Prentice Women's Hospital by Bertrand Goldberg, the book's eight chapters provide a chronological history of hospital architecture, from the Italian Renaissance to twentieth century America. Readers learn about Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Florence Nightingale, E. Todd Wheeler, Eberhard Zeidler, and others who influenced the design of hospitals, as well as the lexicon of plans (panopticon, pavilion, block, mat, labyrinth, etc.) accompanying the evolution of hospitals. But

by Michael P. Murphy with Jeffrey Mansfield and MASS Design Group

Cooper Hewitt, November 2021

Hardcover | 7-1/4 x 10 inches | 256 pages | 250 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781942303312 | $45.00

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

REFERRAL LINKS:

SPREADS: