The Minimal Intervention

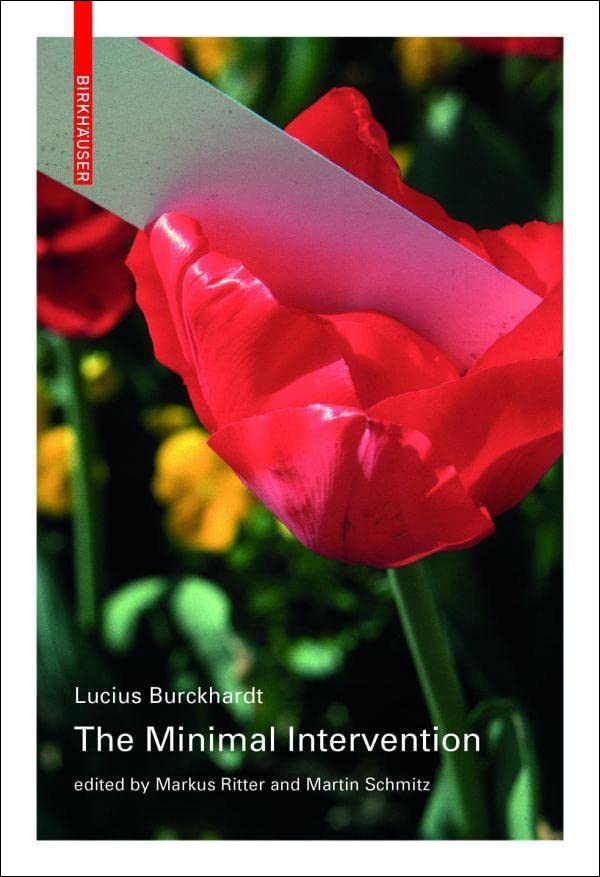

The Material Imaginationby Lucius Burckhardt, edited by Markus Ritter and Martin SchmitzBirkhäuser, October 2022Paperback | 5 x 7-1/4 inches | 166 pages | 13 illustrations | English (translated from German by Jill Denton) | ISBN: 9783035625301 | $26.99PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:Lucius Burckhardt (1925–2003) outlined his theory of the “smallest possible intervention” back in the early 1980s. The idea of minimal intervention runs through his entire oeuvre, from his critique of urbanism to the science of walking. The “smallest possible intervention” denotes a planning theory that assumes two “views” within landscape design: that which is actually visible and that in our mind’s eye. The theory of the minimal intervention means not interfering excessively with the existing landscape, but instead working with the landscape in our minds to develop an aesthetic understanding of the environment. In this book, available for the first time in English, the Swiss sociologist applies this formula to many areas of design.REFERRAL LINKS: REVIEW:Although I can't recall when I learned about Swiss sociologist Lucius Burckhardt, I can pinpoint the first time I read some of some of his texts to the anthology Relational Theories of Urban Form, released last year and reviewed by me last summer. The excerpted texts by Burckhardt in that book focus on "the science of walking," or what he coined "strollology" — a great term that this walker and architectural tour guide has a hard time resisting. Simply put, "strollology examines the sequences in which a person perceives their surroundings," predicated on the fact that every destination is reached by a route, sometimes on foot; we don't just end up in a place via parachute or, in contemporary terms, via Google Street View. That so-called science informed the late sociologist's view of landscapes, buildings, and urban planning, with a strong preference for visual legibility and doing more with less, evident in such assertions as "design is invisible" and "the minimal intervention," the latter being the English translation of a text written by Burckhardt in Italian around 1980, L'Intervento Minimo (it was translated into German in full in 2013 before it was translated into English).The cover, a photograph from the slide archive of Annemarie and Lucius Burckhardt at the University Library Basel (ditto Joseph Beuys, below), hints at the idea of minimal intervention: landscape architect Bernard Lassus would experiment on the altering of perception by placing a strip of white paper within the bloom of a tulip. "Pink-tinted Air" was his expression for the coloring of the paper, which roughly echoes quotes like Louis Kahn's "the sun never knew how great it was until it hit the side of a building" and such buildings as those designed by Luis Barragan, where light reflects off of painted walls to greatly affect spaces. In The Minimal Intervention, Burckhardt sets his sights on planners and the construction industry rather than architects. Burckhardt clearly was not a believer in the merits of highway ring roads, clearing neighborhoods in the name of urban renewal, and the need for elected officials to focus on creating new large-scale building projects rather than the improving the existing building stock. I found myself nodding along with many assertions in Burckhardt's brisk and readable text, which starts in the realm of planning but touches on many aspects of the designed environment — from the design of kitchen appliances to landscape gardening and townscape preservation — across its 150 pages.Joseph Beuys, "7000 Oak Trees," Kassel, 1982–87Near the end of the book, Burckhardt states that "the social mechanisms in decision-making tend to culminate in buildings, [even] in cases where softer strategies would be more effective." Rather than always opting for building, the sociologist argued for a theory where "every issue should be mitigated strategically, by means of intervening in it as little as possible, for this alone serves to minimize the unexpected and harmful consequences." This austere take on planning and design brings to mind the most famous sympathetic instance in recent decades: Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal's project for Place Léon Aucoc in Bordeaux in 1996. The duo found that "the square is already beautiful," so they "proposed doing nothing apart from some simple and rapid maintenance works [...] of a kind to improve use of the square and to satisfy the locals." Referred to often in articles on their Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2021, the landscape was an early expression of an idea that would extend to their more famous and eye-catching transformations of unloved social housing blocks in French cities; I wouldn't be surprised if Burckhardt played a part in Lacaton and Vassal theorizing their minimal approach.Burckhardt uses a number of arguments for an approach to planning that is minimal, but none is more apropos now than the environmental benefits of reusing and t

by Lucius Burckhardt, edited by Markus Ritter and Martin Schmitz

Birkhäuser, October 2022

Paperback | 5 x 7-1/4 inches | 166 pages | 13 illustrations | English (translated from German by Jill Denton) | ISBN: 9783035625301 | $26.99

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

|

| Joseph Beuys, "7000 Oak Trees," Kassel, 1982–87 |

FOR FURTHER READING:

- Lucius Burckhardt Writings. Rethinking Man-made Environments: Politics, Landscape & Design edited by Jesko Fezer and Martin Schmitz (Springer, 2012)

- Why is Landscape Beautiful? by Lucius Burckhardt, edited by Markus Ritter and Martin Schmitz (Birkhäuser, 2015)

- Design Is Invisible by Lucius Burkhardt, edited by Silvan Blumenthal and Martin Schmitz (Birkhäuser, 2017)

- Who Plans the Planning?: Architecture, Politics, and Mankind by Lucius Burckhardt, edited by Jesko Fezer and Martin Schmitz (Birkhäuser, 2019)

- "The Science of Walking" by Lucius Burckhardt, in Relational Theories of Urban Form: An Anthology edited by Daniel Kiss and Simon Kretz (Birkhäuser, 2021)