Parks of the 21st Century

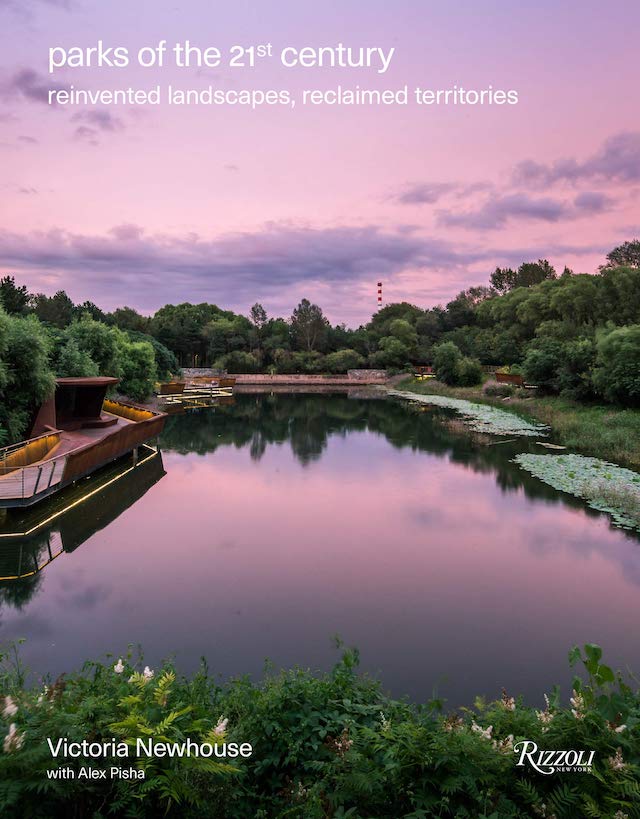

Parks of the 21st Century: Reinvented Landscapes, Reclaimed Territoriesby Victoria Newhouse with Alex PishaRizzoli, September 2021Hardcover | 8-1/2 x 11 inches | 356 pages | English | ISBN: 9780847870622 | $75PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:Parks are essential to our well-being; this has never been clearer than it is today, and a recent surge of park development offers us much to celebrate. Parks of the 21st Century presents 52 parks in the U.S., Mexico, Canada, Europe, and China that have turned despoiled and polluted land (including former factories, railroads, and industrial waterfronts) into beneficial landscapes. Landscape architects have been referred to as “the first environmentalists,” and Parks of the 21st Century shows how parks are being designed as proactive, dynamic green spaces. The High Line in New York is an early example of how an obsolete railroad could be transformed. Opened in 2009, it now attracts nearly 8 million visitors a year. In addition to providing public open space, these renewed landscapes offer economic revitalization and large-scale environmental improvement. Among the parks featured in this book are designs by well-known professionals such as James Corner Field Operations, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Kongjian Yu/Turenscape, and Catherine Mosbach.Architectural historian Victoria Newhouse is the author of Towards a New Museum, Chaos and Culture, and others. Alex Pisha is a landscape and architectural designer for cultural, academic, and civic projects.REFERRAL LINKS: REVIEW:In 1981, Doubleday published The Architecture of the United States, a massive three-volume "guide to American architecture of all regions and all periods" written and photographed by G. E. Kidder Smith. With more than 1,400 buildings visited and documented by the multifaceted architect/critic/photographer, the effort took more than a decade, starting in 1967. His undertaking was enabled by support from the Graham Foundation, primarily, as well as the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ford Foundation, and the Museum of Modern Art; non-monetary support came from his wife, "Dot," who was the driver-navigator on the cross-country trips and did much more in the making of the books. The books are a product of their time, both in terms of an appreciation of the built landscape of the United States (the Bicentennial in 1976 played a part in this, as evidenced by another multi-volume title by Kidder Smith, A Pictorial History of Architecture in America, published that year) and grants being awarded for the creation of what are in effect travel guides.Fuzhou Forest Trail in Fuzhou, China, by LOOK Architects and Fuzhou Planning, Design, and Research Institute, 2017 (Photo: LOOK Architects)I'm thinking of the 1981 books by Kidder Smith in the context of this review because forty years later many surveys of architecture are done at a remove from the subjects they present (I'm speaking from some experience on that) — but not Parks of the 21st Century, whose roughly forty international landscapes were visited by architectural historian Victoria Newhouse and landscape designer Alex Pisha. I can only guess that this contemporary undertaking was enabled by Newhouse's wealth (she is the widow of publishing magnate S.I. Newhouse) rather than the generosity of granting foundations, which these days are geared to academia rather than books like this one with potentially larger, more general audiences. Whatever the case, the fact that Newhouse and Pisha visited each of the parks in the book, usually accompanied by the architects or clients involved on the projects, comes across clearly in the descriptions of the landscapes — and makes the book that much better.Parc Dräi Eechelen in Luxembourg City by Michel Desvigne Paysagiste, 2009 (Photo: MDP Michel Desvigne Paysagiste)The subtitle of Parks of the 21st Century hints at the post-industrial nature of the parks surveyed in the book: the "reinvented landscapes" and "reclaimed territories" occupy former airports, railways, industrial plants, quarries, and other brownfield sites. The book is organized as such, with eight chapters that refer to their former lives: "railways," "highways" (these parks cap existing highways, actually), "airports," two chapters on "waterside industry," one on "inland industry," "quarries," and "strongholds." A last chapter, "future," looks ahead to four in-progress projects, including Freshkills Park in Staten Island. Many of the projects are in North America, with almost as many in China and the rest in Europe. Although this leaves out Australia, South America, Africa, and other parts of Asia, the list of projects is solid, with lesser-known gems found alongside familiar landscapes.Renaissance Park in Chattanooga, Tennessee, by Hargreaves Jones, 2006 (Photo: Charles Mayer)The most famous parks mentioned in the book, but not included as surveyed projects, are Millennium Park in Chicago (opened 2004) and the High Line in New York (phase 1 opened in

by Victoria Newhouse with Alex Pisha

Rizzoli, September 2021

Hardcover | 8-1/2 x 11 inches | 356 pages | English | ISBN: 9780847870622 | $75

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

|

| Fuzhou Forest Trail in Fuzhou, China, by LOOK Architects and Fuzhou Planning, Design, and Research Institute, 2017 (Photo: LOOK Architects) |

I'm thinking of the 1981 books by Kidder Smith in the context of this review because forty years later many surveys of architecture are done at a remove from the subjects they present (I'm speaking from some experience on that) — but not Parks of the 21st Century, whose roughly forty international landscapes were visited by architectural historian Victoria Newhouse and landscape designer Alex Pisha. I can only guess that this contemporary undertaking was enabled by Newhouse's wealth (she is the widow of publishing magnate S.I. Newhouse) rather than the generosity of granting foundations, which these days are geared to academia rather than books like this one with potentially larger, more general audiences. Whatever the case, the fact that Newhouse and Pisha visited each of the parks in the book, usually accompanied by the architects or clients involved on the projects, comes across clearly in the descriptions of the landscapes — and makes the book that much better.

|

| Parc Dräi Eechelen in Luxembourg City by Michel Desvigne Paysagiste, 2009 (Photo: MDP Michel Desvigne Paysagiste) |

The subtitle of Parks of the 21st Century hints at the post-industrial nature of the parks surveyed in the book: the "reinvented landscapes" and "reclaimed territories" occupy former airports, railways, industrial plants, quarries, and other brownfield sites. The book is organized as such, with eight chapters that refer to their former lives: "railways," "highways" (these parks cap existing highways, actually), "airports," two chapters on "waterside industry," one on "inland industry," "quarries," and "strongholds." A last chapter, "future," looks ahead to four in-progress projects, including Freshkills Park in Staten Island. Many of the projects are in North America, with almost as many in China and the rest in Europe. Although this leaves out Australia, South America, Africa, and other parts of Asia, the list of projects is solid, with lesser-known gems found alongside familiar landscapes.

|

| Renaissance Park in Chattanooga, Tennessee, by Hargreaves Jones, 2006 (Photo: Charles Mayer) |

The most famous parks mentioned in the book, but not included as surveyed projects, are Millennium Park in Chicago (opened 2004) and the High Line in New York (phase 1 opened in 2009). Although these projects were not the first of their kind, their phenomenal successes, particularly in the number of people visiting them and the boosting of tourists to their respective cities, made them trailblazers for the transformation of industrial sites into outdoor public amenities. Parks of the 21st Century can be seen as a collection of post-High Line landscapes, even though some of the projects' dates overlap with the famed elevated park. Many more landscapes than the ones surveyed are mentioned by Newhouse and Pisha and often illustrated with photographs, in an effort to provide context for each park and to aid readers in visualizing the references that the authors mention throughout the book; the focus is on the individual projects, in other words, but the scope of the book is much larger.

|

| Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin, 2010 (Photo © Manuel Frauendorf fotografic, courtesy of Grün Berlin GmbH) |

The projects in the book that commanded my attention tended to be ones I'm not familiar with, ones that didn't happen jump off the page as much as others; their qualities were revealed by the authors in their descriptions. One such park is Alter Flugplatz in Bonames, Germany, by GTL Landschaftsarchitektur, the "renaturation" of the Maurice Rose Army Airfield that was built in 1952 and closed forty years later. Inspired by the writings of sociologist and "strollologist" Lucius Burckhardt, GTL devised an approach of "minimum intervention" that "would propagate on its own," per the authors, "while at the same time retaining evidence of the airfield." The photo below illustrates just how that played out between the park's opening in 2004 and the visit by Newhouse and Pisha in 2018: "Moving through the park we discovered a narrow strip of tarmac that acts as a path through what is now a series of woodland rooms [... where] the foot path had become so narrow that we instinctively looked down to keep our footing."

|

| Alter Flugplatz in Bonames, Germany, by GTL Landschaftsarchitektur, 2004 (Photo: Stefan Cop, Photography) |

Such passages describing the authors' firsthand accounts make this book unique in comparison to other surveys, be they of buildings or landscapes. Too much of contemporary architectural writing — books, magazines, online, it doesn't matter — relies on press releases, architects' descriptions, and other available materials in lieu of in-person visits, which are prohibitively expensive. Inserting the experience of the authors into the descriptions allows for more universal "truths" beyond the usual marketing materials that get repeated or built upon in other texts (I'm guilty of this, at times). The value of the visits by Newhouse and Pisha can also be found in elevating the importance of experience in the design of landscapes. In the introduction to my book on landscapes, 100 Years, 100 Landscape Designs, I argued that, while landscape architects are in demand to design places addressing climate change, those places need to be places for people: to exercise, to relax, to socialize, to be in nature. Newhouse and Pisha apparently feel the same way, highlighting post-industrial parks that are important works of landscape architecture — and are places they enjoyed visiting.

FOR FURTHER READING:

- Brooklyn Bridge Park: A Dying Waterfront Transformed by Joanne Witty (Fordham University Press, 2016)

- A History of Brooklyn Bridge Park: How a Community Reclaimed and Transformed New York City's Waterfront by Nancy Webster and, David Shirley (Columbia University Press, 2016)

- Thinking the Contemporary Landscape edited by Christopher Girot and Dora Imhof (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016)

- Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory by Charles Waldheim (Princeton University Press, 2016)

- The Making of Place: Modern and Contemporary Gardens by John Dixon Hunt (Reaktion Books, 2015)

- Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu edited by William S. Saunders (Birkhäuser, 2012)

- Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America by Alan Berger (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006)

- Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture by James Corner (Princeton Architectural Press, 1999)